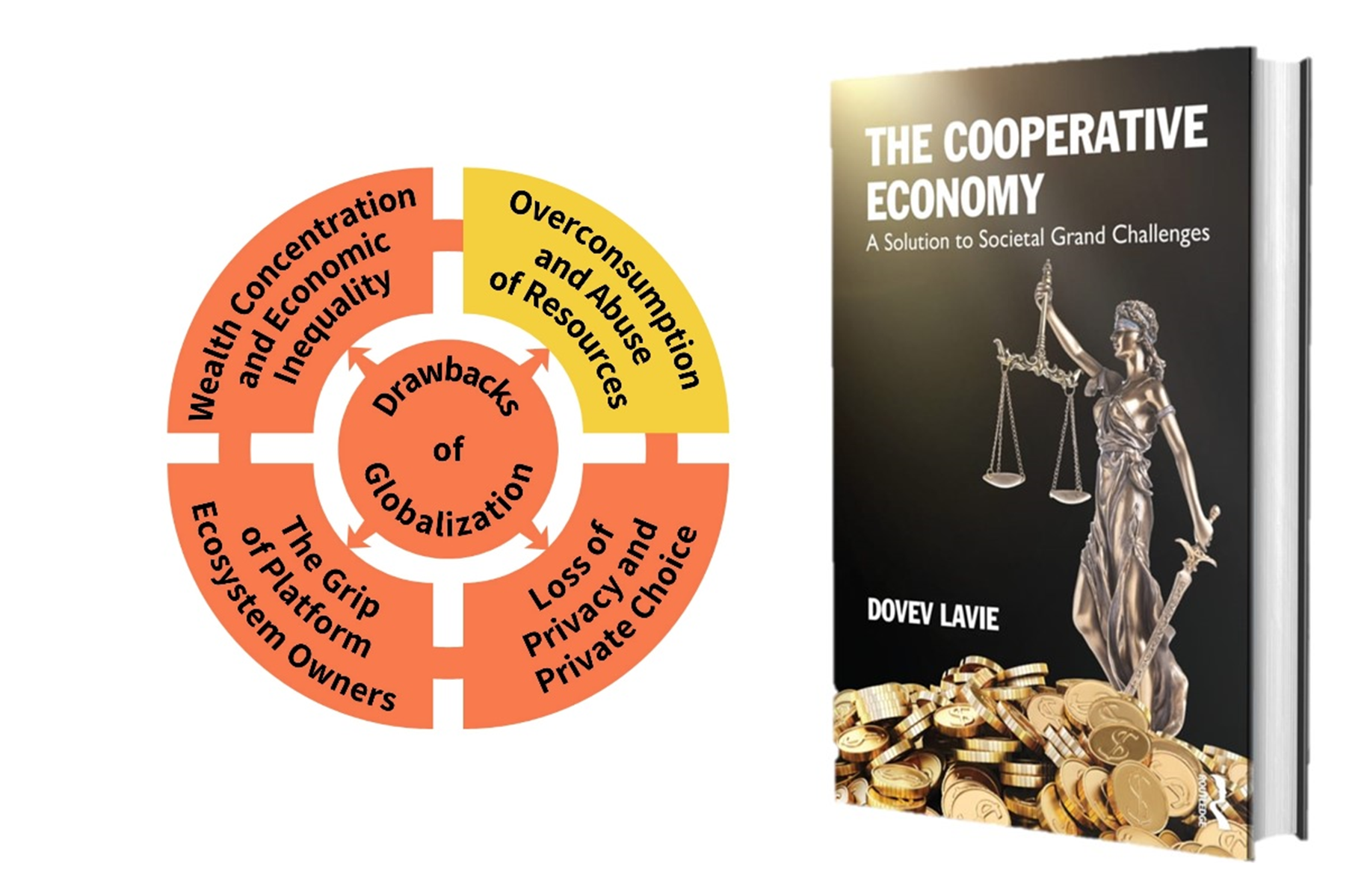

The free flow of goods, capital, and labor has many merits, but not everyone can enjoy the gains. Globalization has fostered economic inequality by increasing the return on capital while depriving the underprivileged, who have remained immobile and taxable. Multinational corporations have leveraged globalization to specialize, optimize supply chains, reduce costs, and evade taxes, while gaining power relative to governments. National policies have fallen short in responding to job loss, brain drain, flux in international migration, and unemployment. Globalization has promoted consumerism and overconsumption while making financial networks and supply chains more vulnerable, as demonstrated by the mortgage crisis in the United States, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the war in Ukraine. Moreover, the individualistic culture promoted by globalization has challenged societal values and otherwise cohesive social structures.

In devising policies, international associations find it difficult to reach a consensus given the diverse interests of member states. Governments have been unable to balance economic forces and free trade with societal and environmental motives. Attempting to transplant societal values into multinational corporations with a for-profit mission is unlikely to succeed. Thus, a recent OECD report admits that “we urgently need to fix globalization, but we don’t fully know how to do so.” The drawbacks of globalization have exacerbated the problems of the modern economic system. It is time to consider a new approach to cope with the drawbacks of globalization. I discuss such an approach in my book The Cooperative Economy. For more information visit the book’s website.

With their relentless profit-seeking, firms have not only exploited stakeholders but also abused our planet’s natural resources by leveraging advertising that spurs overconsumption. In the past century, the exploitation of raw materials has increased by 650 percent, and the extraction of natural resources has increased by more than 300 percent in four decades. The population of animals declined by almost 70 percent during that period, in which the land, air, sea, and rivers have been polluted, with global warming prompting natural disasters. And while a quarter of produced food is wasted, in deprived regions, many experience hunger. Consumers have also done little to change their habits and become more mindful about the unfortunate consequences of their lifestyles. At the current rate of consumption, by 2050, 2.5 planets will be needed to supply demand.

It is mostly the affluent nations and individuals that overconsume, restricting the availability of finite natural resources to others. Firms have trained us to consume to satisfy emotional desires rather than physical needs, but happiness is beyond reach for those falling into this trap. Many firms proudly exhibit their environmental peacock feathers, only to lure consumers with their greenwashing to make extra profit. Some firms have improved their production processes by incorporating alternative energy sources and recycling. But although such supply-side initiatives have been fostered by regulation, responsible consumption has not. Responsible consumption and voluntary simplicity remain slogans, and no consumption caps have been set by policymakers. Reducing consumption is likely to restrict consumers’ utility and firms’ profits while jeopardizing the economic growth of nations, so all stakeholders have a shared interest in enduring overconsumption. Thus, by 2030, with the exhaustion of natural resources, shortages and catastrophic weather conditions are likely to become more prevalent.

It is time to consider a new approach to cope with the overconsumption and abuse of natural resources. I discuss such an approach in my book The Cooperative Economy. For more information visit the book’s website.